To mark the end of 2012, a somewhat bumpy year for Tunisia’s political transition, the Tunisian Ministry of Finance organized a spectacular event: a public auction and sale of goods and trinkets nationalized from Ben Ali’s private palace in Sidi Dhrif, a palatial home overlooking the Bay of Tunis and the idyllic sea side town of Sidi Bou Said. Simply named Confiscation, the event was widely advertised around Tunisia with a website showcasing objects to be sold off to Tunisia’s public beginning on 23 December 2012. To display the confiscated objects ranging from interior décor, a luxury car collection, and designer clothing, handbags and shoes formerly worn by Tunisia’s notorious former first lady, Leila Trabelsi, the organizers opted for the Espace Cléopâtra in the wealthy touristic zone of Gammarth in Northern Tunis. Those interested in viewing the confiscated collection or purchasing luxury ex-dictatorial paraphernalia are required to purchase tickets online, at thirty Tunisian dinars (approximately twenty U.S. dollars), or just below ten percent of an average monthly Tunisian salary.

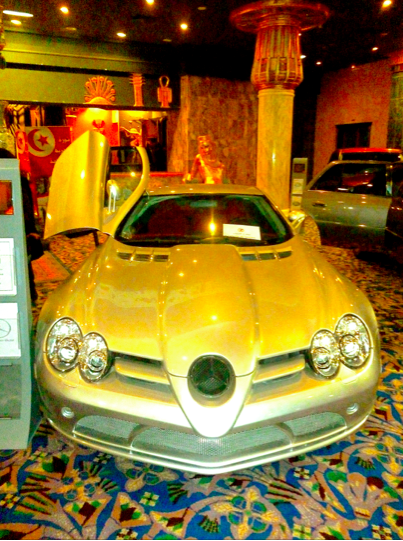

Additionally, visitors must purchase tickets by Tunisian credit card, a payment method exclusive to Tunisia’s upper income brackets. The venue itself mirrored the goods displayed – an ostentatious and gaudy exhibition hall adorned with hieroglyphs, embellished with golden representations of pharaonic Egypt. The exhibition was divided into four sections: (1) Ben Ali’s and Sakhr El Materi’s extravagant luxury car and boat collection constituting the entrance, (2) flashy home décor including gold, silver, and crystal statues along with Ben Ali’s and Leila Trabelsi’s exclusive jewelry, (3) finely woven silk carpets and traditionally crafted Tunisian furniture, and (4) Leila’s dazzling designer fashion collection resembling Saks 5th Avenue’s first floor in NYC. Confiscation was indeed awesome, not only for its utmost bizarre exposition, but also for the diverse sentiments and critiques the event attracted from Tunisian citizens.

[Leila Trabelsi`s accessories. Image taken by Laryssa Chomiak and Robert P. Parks.]

Justification de l’Etat: Chronicles of a Cash-Strapped State

The Ministry of Finance promoted the event as an attempt to recuperate stolen state resources and pump the proceeds back into Tunisia’s ailing economy. Despite the hype, the event is projected to bring in only twenty million Tunisian dinars (ten million euros), which would hardly cure the country’s real economic pains. Among them are an official unemployment rate just short of twenty percent (unofficial numbers are more than double) and increased job losses in the foreseeable future. Nor does the highly publicized event mirror the state-led sale of former industries owned by the Ben Ali-Trabelsi clan, including a fifteen percent stake of the telecommunication firm Tunisiana[1] (for 360 million dollars) to Qatar Telecom, constituting ninety percent of shareholding on Tunisiana. Just this week, the government began selling the Ben Ali family’s sixty percent stake of Ennakl, the automobile firm selling luxury vehicles including Porsche, Seat, and Audi, percent to the Poulina-Parenin Consortium – a Poulina Group Holding and Ben Yedder Group joint venture. Yet at the same time, TunisAir, the state-run airline company, just announced 1,700 lay-offs in early 2013. While Confiscation, the high-end flea market of dictatorial kitsch, might propel some consumer activities, it seems unlikely that the highly publicized and pompous affair is all about finances. The sale, its procedures, and location carry a much higher symbolic value, where an increasingly unpopular post-revolutionary regime is desperately searching for avenues to increase, if not create, political legitimacy among a disgruntled population. And what better avenue but to present ordinary Tunisian citizens with the untouchable, materialistic, and extravagant past defining the lived dictatorship of Zine Abedine Ben Ali, Leila Trabelsi, Sakhr El Materi, and other close family members – a past once only known through popular rumors, snippets of clandestine images and stories, and later Wikileaks accounts infuriating millions of citizens.

Who Buys this Stuff?

Despite a significant media campaign that aimed to increase public awareness, widespread participation at the expo-sale appears to be restricted by location, cost, and procedure. Security measures precluded organizing the event in downtown Tunis, or at the expo-center just north in Le Kram - both occasional sites of violent political contestation during the transition period. Lacking a secure alternative, the Ministry of Finances hosted the event at the Espace Cléopâtre expo-center, in Gammarth. Home of the current and former Tunisois economic and political elite, including Moaz Trabelsi, one of Leila Ben Ali`s nephews implicated in an international yacht-theft ring, Gammarth is one of Tunisia’s most exclusive residential destinations as well as a tourist zone. Correspondingly, it has limited public sector transportation. A Tunisian living in southern or downtown Tunis could spend up to three hours on the round-trip journey via public transportation, while round-trip cab fare costs about thirty Tunisian dinars (twenty dollars).

[Sakhr El Materi`s boat, outside Espace Cléopâtre. Image taken by Laryssa Chomiak and Robert P. Parks.]

[Hall 1, Espace Cléopâtre. Image taken by Laryssa Chomiak and Robert P. Parks.]

Getting a day pass is perhaps more onerous than transportation costs. Limited to five hundred a day, passes cost thirty Tunisian dinars, and can be purchased neither at the gates nor in cash, as we discovered. Tickets are only available online with a Tunisian credit card at the website. Even though internet usage in Tunisia increased from six percent in 2003 to thirty-six percent in 2010, the International Telecommunications Union reports that fewer than forty percent of Tunisians accessed the internet in 2011. Access to the banking system too is limited. While Tunisians have greater access to bank accounts than their neighbors in Algeria or Libya, most account activities are limited to over-the-counter deposits and withdrawals. Fewer Tunisians have checking accounts, and fewer still a credit card.

Combined, the transaction costs for an average Tunisian to attend Confiscation include time spent finding a friend with a credit card, a wait, user fees at the local cyber café, thirty Tunisian dinars for the ticket, and either another thirty Tunisian dinars for cab fare or two to three hours in public transportation. Location, cost, and procedure limited widespread public access to an event ostensibly meant to underscore the current transitional coalition government’s commitment to transparency and citizen accessibility.

Though an expo widely publicized to highlight Tunisia’s revolution and an attempt to reconcile Tunisian citizens with their dictatorial past, the target audience was hardly the working class from Sidi Bouzid, the Gafsa Mining Basin, or even the southern Tunis suburbs – regions that have been invariably (and perhaps erroneously) assimilated to the January 14 uprising or entrenched Nahda support. Nor did the event rally Tunisia’s traditional economic elite. Perhaps in beldi (Tunisia’s historic and cultural bourgeois) fashion, the wealthy avoided the ostentatious display of the former regime’s wealth either out of fear of assimilation, or by revulsion at the vulgar sale of the former dictator’s belongings – to “les grandes familles” it is considered both uncouth and unlucky to purchase seized goods. Judging from the models of cars parked near the roundabout at the entrance to the expo-center, as well as the dress of event-goers, attendance drew primarily from the upper-middle classes, who seemed particularly interested in Ben Ali’s carpets and Leila’s flashy handbags.

[An amethyst horse statue from Sidi Dhrif residence and silver bowl accessories from Sidi Dhrif residence. Image taken by Laryssa Chomiak and Robert P. Parks.]

Spectator Reactions

Many Tunisians increasingly express that the event is a vapid celebration or sinister mockery of both revolution and reconstruction. Instead of elaborately staged publicity events, such as Prime Minister Hamada Jebali cutting the ribbon at the 22 December VIP opening ceremony, many Tunisians noted that the government should be working to promote real foreign investment and public works projects, pointing to the recent inauguration of the Casablanca light-rail system, attended by Mohammed VI and French Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault. With unemployment at all-time highs, many ask whether Tunisians were invited to the event at all. Tunisian minimum wage is 320 Tunisian dinars a month, whereas the cheapest items for sale (not to mention ticket and transportation costs) run no lower than 150 Tunisian dinars. Many more Tunisians believe Saudi and Qatari businessmen invited to the 22 December VIP inauguration constituted the real target audience. Conspiratorial narratives take this further: Qatari businessmen confirm unseemly political-economic deals between the Gulf States and Nahda, while Saudi buyers are Ben Ali’s straw men sent to buy back his property with the gold his family is said to have transferred from Tunisia’s Central Bank during the days immediately before 14 January.

[Lion statues from Sidi Dhrif residence. Image taken by Laryssa Chomiak and Robert P. Parks.]

For those who did attend, the reactions were a masked ambivalence. The halls of Confiscation were eerily silent – not withstanding the odd choice of a heavy metal house soundtrack to go with the videos displays documenting Ben Ali’s different properties and possessions on loop-feed. Conversation was muted. Whether the silence reflected lingering anger or fear Ben Ali’s specter might conjure or whether it reflected the uneasiness or shame of symbolically devouring the fallen dictator-patriarch’s assets remains unclear. When a journalist from France Inter approached the sales line to ask about how people felt purchasing Ben Ali’s possessions, one woman said: “I’m proud to own this. This was purchased with Tunisian money, and I’m purchasing it with mine.” When asked if she could be filmed, she and everyone around her demurred, looking at the floor, out of embarrassment. One witness to the scene later stated, perhaps holding to the beldi framework, that the sale was cannibalism: the very Tunisians who could afford to attend had been the foundation of Ben Ali’s support. Purchasing his goods was either cannibalizing the father figure or feasting on his remains. Stolen property, even when re-sold to those from whom it was taken, remains at the least stolen property, if not and perhaps more profoundly an object of public shame.

Conclusion

Despite the Ministry’s intentions to “re-invest” Ben Ali’s illicitly gained possessions back into the Tunisian economy in a transparent way, Confiscation does not seem to have been the domestic success the transitional coalition had hoped. Popularly held conspiracy theories tarnish the transparency, a widespread perception that purchasing stolen items brings bad luck, with location, cost, and procedures that limit participation, all render the whole process somewhat unseemly, not to mention the awkward process of extracting citizen’s personal resources for objects that were acquired with public funds. “Why should Tunisians pay for something that was taken from them,” our friend asked just a few days back.

If anything, Confiscation stirred the reactions and emotions of Tunisian citizens who daily navigate the memories of a dictatorial past and concerns of an uncertain presence, while facing problems of security, economy, and political stability. Like any other post-dictatorship, Tunisians have to undergo a process of reconciliation with an illiberal and corrupt political past that extended its tentacles into the everyday lives of its citizens, from schooling to the workplace to social spaces. The political and economic omnipresence of the Ben Ali regime coupled with its almost complete penetration into the daily lives of Tunisians pushed ordinary citizens to demand its end. To reconcile Tunisian citizens with that past via a flashy Expo staged by the Ministry of Finances does not seem as peculiar as the event’s timing – just weeks before the two year anniversary of the 2011 Tunisian Revolution at a time of widespread economic worries and soaring unemployment. While foreign visitors disconnected from Tunisia’s dictatorial past wander the halls of Espace Cléopâtra and either purchase goods unabashedly or enjoy the experience of a glimpse into the life of a fallen dictator, Tunisian citizens are confronted with the paradox of an opportunity to repossess the dispossessed. Whatever the frustration, we need not forget that only two years ago, any political spectacle of such magnitude would have never allowed for even a smidge of public criticism. The explosion of public mockery, shame, disgust, frustration, sarcasm, and confusion is at the very least an important move towards demystifying one of the most brassy and audacious authoritarian regimes of the last two decades.

[1] Tunisiana was acquired by Sakhr El-Materi just days before the 14 January 2011 Revolution.